Where did these deer come from? Indiana Deer History.

Dec 24, 2017 8:00:16 GMT -5

saltydog, jjas, and 4 more like this

Post by Woody Williams on Dec 24, 2017 8:00:16 GMT -5

WHITE-TAILED DEER

John M. Allen, Project Leader Project W-2-R

Most wildlife species present today have persisted because of, or In spite of numerous influences operating long before biolo¬gists were able to record them. We can only surmise how the passenger pigeon, bison, and otter reacted to the environment of Indi¬ana. Not so the white-tailed deer, for after being totally "wiped out" they were given a fresh start in 1934. This provided the rare opportunity of following the fortunes and misfortunes of this restored native. Ex¬periences of other states and information collected at home on our growing herd were pooled to prescribe management practices assisting the adjustments necessary before they could take their place as Indi¬ana's only big game animal.

Some progress has been attained in whitetail management, but it is doubtful if a permanent and unyielding solution for all ills will ever be formulated. It is hoped that we can anticipate problems associated with deer management and provide answers before difficulties arise.

As is the case with many wildlife species, management of the ani¬mal is far less difficult than associated problems of man-management. Until administrators, hunters, and landowners are aware of the poten¬tialities and reactions of growing deer herds, management recommen¬dations will be of limited value.

CHARACTERISTICS

Our white-tailed deer are members of a distinguished family in¬cluding elk, caribou, moose, mule deer, and black-tail deer. While there have been rumors of mule deer moving into our southern counties from releases in Kentucky, none have been found, and we can assume that our only deer is the whitetail. .

As to dimensions, ours are large in comparison to those of many other regions due to better food conditions; however, deer sizes are nearly always overestimated. Weights vary with sex and age of the animal, but average weights of approximately 1,000 adults and fawns, bucks, and does, examined at checking stations indicate that the "aver¬age" male weighed 157 pounds live weight and his female counterpart but no pounds. Three splendid bucks were taken during the 1951hunting season. One weighed 329 pounds before dressing; the other two were cleaned before weighing, but would have exceeded 300 pounds live weight.

One of the most interesting features of the male is his rack of antlers. Contrary to popular belief, they are not indicators of age, but rather they reflect the animal's physical condition. In general the diameter of antlers increases with age, but a well-fed 4 year old may have a much larger rack with more points than an 8 year buck in poor physi¬cal condition. Antlers fall off each year between January and March much in the same manner as do leaves. New ones start to emerge at once and quickly replace those lost but they remain soft until late sum-mer when they harden and are polished on small trees and bushes.

Deer, like cattle, have no front teeth on their upper jaw and break their food off rather than bite it. Similarly, they are ruminants and have 4 stomachs, but unlike most others they have no gall bladder. They frequently swallow acorns and grain whole, then regurgitate, chew, and swallow at their leisure.

Does are bred in October and November and after 205-212 days gestation, drop fawns. Their reproductive powers are usually under¬estimated as 25 does would have 3,000 descendants in 10 years if all survived. They add 25 to 35 per cent to their numbers each year thereby compensating for an annual loss by legal and illegal kills, dogs, and automobiles. In fact, when a herd is not increasing each year it indi¬cates a mortality factor worthy of investigation. It has been estimated that the 1955 Indiana herd should number 20,000 animals instead of 5,000. Illegal kills of both sexes were a serious limiting factor when the herd was first, becoming established a few years ago.

Their color changes with the seasons as their reddish summer coat is replaced by a gray one in autumn. Fawns are born with light colored spots on a brown background serving to camouflage them, but this coloration fades to match the gray of their parents in early fall . Deer were formerly regarded as an animal of the deep forests but their rapid increase throughout the Midwest in the past two decades has revised our ideas of what constitutes deer range. This is but another example of how some animals have adapted themselves to changing con¬ditions. They now thrive at the very edges of large metropolitan areas and inhabit farmlands boasting of little cover other than inconspicuous woodlots. When whitetails first began their population climb in Missouri, Ohio, Iowa, and other Midwestern states, game managers believed only hilly country could be occupied. Each year their range has been ex¬tended until now it is more difficult to predict where they will not thrive than where they will.

A deer's life can be a hazardous one for ancient predators such as wolves and mountain lions have been replaced by modem ones. Illegal killing of young and old throughout the year has, in some counties, prevented their increase and in a few has nearly destroyed the devel¬oping herds. Loose running dogs take their toll, particularly in the spring when does are heavy with fawns. It has been demonstrated many

times that hunting dogs of various breeds and curs can and do run down and kill even adult bucks. Many miscellaneous accidents such as drowning, collisions with fences and autos, and falls over cliffs are the result of dog chasing. These mortality factors are probably not too important to a large herd but seriously limit the successful establishment of small herds such as ours.

Open deer hunting seasons have probably helped deter illegal kills more than is commonly recognized. Merchants and farmers alike dis¬covered that a deer in the field is worth many in the meat house, as deer bring hunters, and hunters spend money. Increased efficiency of the enforcement section has paid off in a marked decrease in deer law violation. Considerable credit is due the group of conservation officers and forestry personnel who have contributed much to protect our herds.

Whitetails are primarily browsers although they graze winter wheat, rye and spring grasses. Their diet leans heavily towards leaves, fruits, and tender twigs of most common weeds, shrubs, and tree seedlings. Acorns are the backbone of their winter diet, but no one can deny that they turn readily to grain and hay and when the mast crop fails. Some damage to green corn and soybeans has been experienced in mid-summer in localized areas. Damage is most severe in small fields bordering wood¬lands and occurs most frequently during winter months so losses can be curtailed by harvesting crops as soon as possible after they ripen. Bucks like to polish their antlers on small trees and during the breeding sea¬son stage fights with imaginary opponents, usually small trees. Some damage to fruit trees has been caused in this manner and has been successfully prevented by spraying with commercial deer repellents and scaring devices such as foil streamers. Consumption of their pre¬ferred foods such as poison ivy, sassafras, mints, plantain, honeysuckle, greenbriar, sumac, and wild grape can scarcely be cause for complaint.

Disease and parasites have not been prevalent here nor responsible for deer loss. Lung worms, sometimes common in deer farther north have not been found here, and "hemorrhagic septicemia," the deer disease of the South, has occurred only on a small scale. They live to a ripe old age as shown by ear tagging those released. Two ear tags were returned by hunters in 1951 and one in 1952. These animals had been released in 1941 and were a year old at that time. Tame deer may live 15 years, but wild ones seldom escape the "grim reaper" that long. In the snow belt of states and provinces of the north, food supplies and snow drifts frequently determine how many deer can be carried through the winter. Deer congregate in "yards" and consume all avail¬able food in this limited area, causing the weaker ones to starve. Rela¬tively mild winters here permit deer to utilize the same range both winter and summer, and starvation is unknown.

EARLY HISTORY

At the time Indiana was settled, the northern whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus) was widely distributed over the state. This territory was covered with hardwood forest with the exception of the larger prairies, swamps, and lakes extending across the northern portion of the state. As many as 1,130 hides were purchased by a fur dealer in Hamilton County in 1859. Carl Sandburg's biography of Abraham Lincoln quotes as follows: "In 1820 Noah Major, one of the first settlers in Morgan County, Indiana, estimated there were 20,000 deer in the county." They were plentiful in the Kankakee region and there are reports of 65 being killed in a single day in 1878. The last stand of deer in the state was in the Kankakee region and in Knox County where the last known wild deer was killed near Red Cloud in 1893.

RESTOCKING

Removal of timber from steep hillsides produced violent results in the south central hill country. Farmland was soon abandoned as top soil washed away. Much remains in private ownership, but state and federal governments now own approximately 235,000 acres in this section.

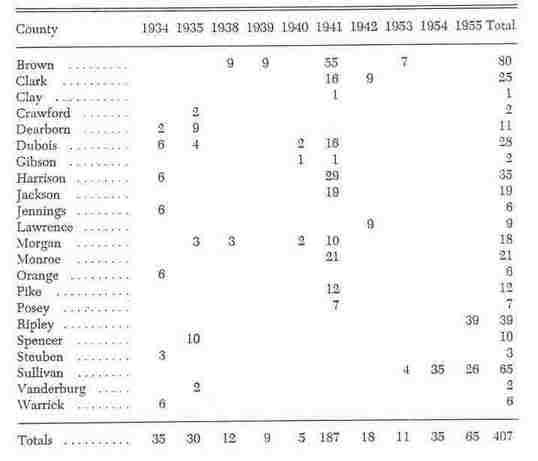

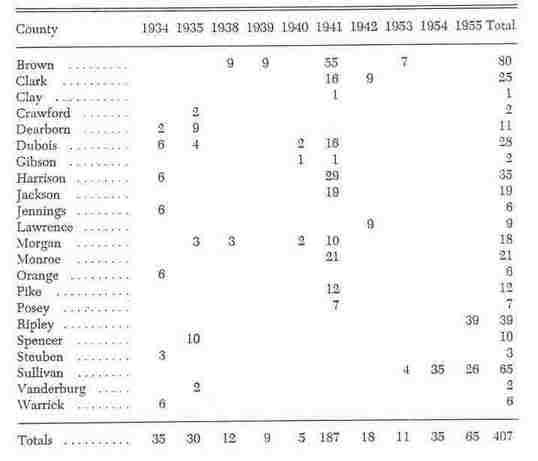

In the early 1930's the Indiana Division of Fish and Game became interested in the possibilities of this territory for forest game. In total, 296 whitetails were released during the period 1934 to 1942 (Table 5). Of this number, 91 were released between 1934 and 1940 and 205 in 1941 and 1942. Many of the earlier releases were made on both state and privately owned land. Liberations were principally confined to the unglaciated hill country of the south central section, with minor releases to the east and west. Deer used for restocking were obtained primarily from Wisconsin but some were purchased from Michigan, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina. This stock was comprised of some southern whitetails, northern whitetails (Odocoilius virginianus borealis), and mixtures of these two sub-species.

Original liberations in the south central section were successful enough to initiate deer hunting there in 1951, where an open season has been held every year since that date. It soon became apparent that the limited occupied range could not accommodate all the hunters without greatly reducing the herd unless the season was limited in duration and sex to be hunted. The answer was to extend the occupied range so that hunting pressure could be dispersed over a much larger area. Surplus deer were removed from state owned exhibits in 1953 and 11 were released.

The Woodland Game Development Project purchased 100 white¬tails from the Schowalter Deer Farm in Wisconsin. These animals, half of which were does, were released on the east and west flanks of the occupied deer range in order to eventually provide more deer hunting territory.

Figure 7-0ne of the first deer releases. Harrison County State Forest 1934. (Photo by Dewey Hickman)

A release of 35 of these deer was made in Sullivan County on Greene-Sullivan State Forest where there is an abundance of suitable range in and surrounding this forest. In January 1955, a total of 26 was liberated on Shakamak State Forest in Sullivan County to further ex¬tend the herd in the southwestern portion.

In order to establish a herd in the southeastern section, 39 deer were released on Versailles State Park in Ripley County in February 1955 (Table 5). The counties in which these animals were released will be closed to deer hunting for a period of at least five years to per¬mit herds to develop. At the end of that period they and adjacent coun¬ties will be open to hunting if warranted by herd increases.

TABLE 5

WHITE-TAILED DEER LIBERATIONS IN INDIANA, 1934-1955

THE BEGINNING

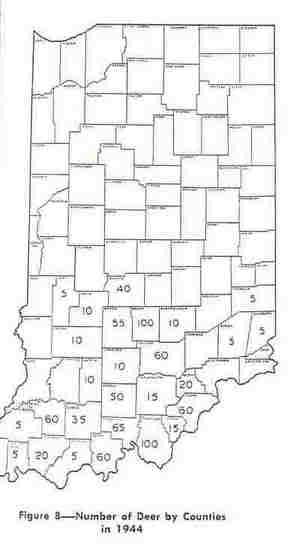

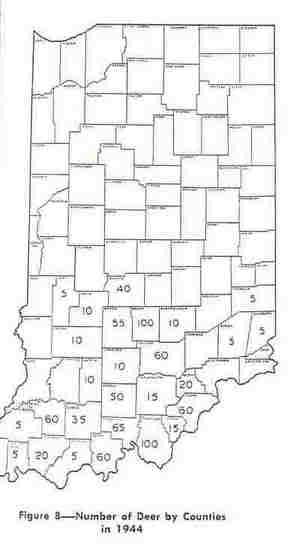

Following the releases of 1941 and 1942, WID. B. Barnes started gathering information on the growth of our new herd. By interviews with local residents and state personnel, the 1944 population was found to be 1,200 animals as com-pared with 900 in 1943 (Figure 8). They had extended their range into 35 counties, three of which had herds of 60 to 100 deer. The headquarters for larger herds re¬mained on state forests or parks with the exception of small but growing herds in the strip mines of Pike and Warrick Counties and on private land in Orange County.

Few people, not intimately as¬sociated with deer, realize their reproductive powers. More than one-third of our female fawns are bred at the age of 6 months and have produced another fawn by the time they are a year old. Ma¬ture does nearly always produce twins each spring and triplets oc¬cur frequently. Barring excessive illegal kills, herds were destined to extend their range and numbers by leaps and bounds. By 1946 there were approximately 245 deer in counties outside principal deer range, while 18 counties within principal deer range, supported herds totaling 2,700 animals. This figure was conservative as some local residents and state employees believed that 500 to 1,000 animals were present on Brown County Park, with equal numbers on state forests, U. S. Forests, and U. S. Military Reservations.

A deer drive was conducted in November 1946 on Harrison State Forest with the aid of interested landowners and sportsmen. Seven bucks and 19 antlerless deer were Hushed from a 700 acre tract, con¬sidered to have been one of the most heavily populated ranges in the state. This would indicate 1 deer per 27 acres in part of the forest. If the entire forest was as heavily populated as the area driven, the forest population would have been 630 animals. Since a major portion of it supported a much lower population than the area driven, it is doubt¬ful if more than 350 animals were present in the entire county at that time.

Aerial deer counts have been utilized with varying degrees of suc¬cess throughout the nation, so in February and March 1947, this method of counting deer was tested on an experimental basis. Flights totaling 20 hours were made over Harrison State Forest, Brown County Park, and in Orange County. That observation prior to February was impaired by leaves remaining on trees of the white oak group. Cedar trees and pine plantations greatly limited observation where present. Under Indiana conditions, an aerial survey can be utilized only, if at least two inches of snow covers the ground, and if the wind velocity does not exceed 10 miles per hour. The experiment showed that the aerial census with conventional aircraft has very limited use over the major portion of our principal deer range.

By 1946 the novelty of seeing deer had passed. Damage to small grain, corn, hay, truck crops, and orchards was reported with increas¬ing frequency. A shootable population had developed in small seg¬ments of the range, but insufficient areas had reached this stage to justify the open hunting season. Illegal hunting became a problem of major importance.

COMPLICATIONS

The manner in which all animals, large or small, mesh into their environment is indeed complicated. In fact, many of the relationships between any game animal, and other plants and animals, including man, are unknown. It is understandable that re-introduction of even a native game animal is seldom accomplished without some conflict of interests.

In order to assist this adjustment it became apparent that the Con¬servation Department must collect as much information as possible on the growing herd. The White-tailed Deer Investigation was initiated in December 1949. This study was designed to map occupied deer range, to estimate herd size, and to devise methods of censuring deer on uninhabited forest tracts where farmer-interview census methods were not effective. Deer losses through illegal kills, dogs, and highway accidents were occurring at an unknown but increasing rate. Crop damage was severe in some localities but was greatly exaggerated and used as an excuse for illegal killing in widespread areas. We were now in the awkward position of having many deer in rather localized areas capable of sustaining crop damage, but not enough deer range to open a season so that legal hunters could scatter herds and reduce crop damage. It was necessary that hunt plans be formulated for the time that a hunting season could be held.

Eleven major herds were mapped in 1949 within principal deer range. Herd sites varied considerably in character, but they possessed one common feature-a refuge from men and dogs. None were formal inviolate tracts, but had been established for timber production, recrea¬tion, military use, private estates, or coal mining. Minor exceptions were portions of the Orange County and Muscatatuck herds.

The Morgan-Monroe herd became established on Morgan-Monroe State Forest, and occupied parts of Morgan, Monroe and Brown Coun¬ties. The Brown County herd developed in Brown County State Park and extended into Lawrence, Jackson, and Brown Counties. The Mus¬catatuck-Knobs herd started from deer released on Jackson and Clark State Forests, and by 1949 projected into 6 counties. The Orange ¬Martin herd extended into Lawrence, Greene, Martin, and Orange Counties. The Blue River Herd was located in both Harrison and Craw¬ford Counties, but was restricted largely to Harrison State Forest. The Lafayette Herd was limited to Perry County and originated from re¬leases made on U. S. Forest Service land . The Ferdinand herd was developed on Ferdinand State Forest in Dubois County, but extended into Perry County. The Strip Mine herd centered on coal company land in Pike, Warrick, Dubois, and Gibson Counties.

Farmers were interviewed throughout the deer range in 1950 to determine the extent of deer damage to crops, to obtain their opinions on an open season, and to estimate deer numbers. About two-thirds of them had never sustained damage, three-fourths favored an open season, and nine-tenths of them were in favor of having deer in their area.

The 1949 population census showed 2,540 animals, of which 300 were in counties scattered over the state and outside the principal range in the south-central hill section. Due to illegal killing of bucks and does, young and old, there were fewer deer in 6 counties than in 1946, but most of the herds showed a gain.

FIRST OPEN SEASON

The White-tailed Deer Investigation had progressed to the point in 1951 that we knew where the deer were, approximately how many, something of their rate of increase, and limiting factors. Many of the basic facts necessary for proper management were still unknown but it became increasingly apparent that an open hunting season was needed to scatter herds, relieve crop damage, and curb illegal kills. The 1951 population estimate was 4,943 animals, quite an increase from 1944. About 4,500 of these were in 17 counties which were believed to be ready for an open season.

The 1951 General Assembly gave the Director of the Division of Fish and Game discretionary powers to issue orders regulating the hunting and killing of deer. A hunt plan including regulations was form¬ulated and submitted to the Director of Fish and Game.

The first open deer hunting season in 58 years was held November 1, 2, and 3, 1951. In brief, it was an "any deer" season in 17 counties, with shotgun slugs and bow and arrows only. The number of licenses sold was not limited. They were issued at a cost of five dollars to resi¬dents only. Information on the hunt was collected by compulsory re¬turn of postal card reports issued with licenses, while Pittman-Robertson personnel and conservation officers manned 6 checking stations in 5 herd areas where successful hunters were interviewed and deer examined.

Nearly everyone agreed that the open season was an unqualified suc¬cess. Consideration and cooperation of hunters and landowners was above reproach. It was characterized by splendid landowner-hunter relations, a high degree of gun safety was maintained, and hunters were well pleased. In total 633 deer were brought to checking stations where they were hog-dressed, weighed, and age determined by tooth-wear charts. In total. 12,182 licenses were sold; 10,002 licensees returned hunt reports.

Farmers hunting on their own land without licenses were reported by conservation officers to have killed 32 animals. Licensees reported bagging 1,558, thus the total known kill was 1,590 bucks, does, and fawns. This indicates that 13 per cent of the licensees were successful. Bows and arrows could be used in any of 17 open counties and approxi¬mately 8,600 acres of Brown County State Park were open to archery hunters only. Three deer were taken by archers, one by a 14 year old lad. About half the deer taken were bagged on the first day of the hunt, while on the second and third days, 24 per cent and 25 per cent were recorded. Greatest success was attained between 7 A.M. and 11 A.M., as more than half of the kills were made during these hours.

Based on interviews of 633 successful hunters, each man hunted about a day and a half, saw 3 1/2 deer, shot at I 1/2, and hit one. The average range on the first shot was 48 yards. Evidently the shotgun slug was effective, for 47 per cent of the animals dropped in their tracks, 36 per cent ran 1 to 50 yards, 15 per cent ran from 51 yards to a half mile, and 2 per cent ran farther than a half mile before dropping.

Adult bucks comprised 39 per cent of the kill; adult does, 30 per cent; and fawns, 31 per cent. Considering both adult and fawns, bucks constituted 55 per cent of the kill.

Both entire and hog-dressed animals were brought to checking stations for examination. Weights before and after hog-dressing, in¬cluding removal of heart, liver, and lungs, indicated that adults lost approximately 18 per cent, and fawns 20 per cent in gutting. Total length from tip of nose to tip of tail bone and hind foot measurements were taken to compare skeletal development of deer in different herds. Antler development was similarly utilized to compare condition of the animals and indirectly indicated the quality of range used by different herds. A number of bucks with 16-20 antler tines was recorded. Spurs on freak sets were not counted as points.

The most outstanding fact revealed by this intonation was that deer from the Blue River herd were smaller boned and weighed less than those of the other 4 herds sampled. It had been suspected that this area was overpopulated and that over-browsing was becoming an immediate problem. The superiority of the mixed range of the Strip Mine herd was reflected in above average weights and measurements in most age classes. Bucks continued to gain weight until about 7 ½ years old, but does weighed nearly as much when 2% years old as did older specimens.

A number of large animals was taken from all herds. Bucks in the 5 ½ year age class from all areas averaged 191 pounds dressed and had 10 antler points, while those in that class from the Strip Mine herd averaged 243 pounds. One buck examined at Morgan-Monroe State Forest weighed 270 pounds and another 269 pounds dressed. The largest doe examined was taken from the Strip Mine herd; was 2 ½ years old; and weighed 156 pounds dressed, or 190 pounds live weight. The weight of deer is usually overestimated as four and five hundred pound bucks reported by local residents did not materialize at the scales.

The immediate task of the deer investigation was to evaluate the effects of the first hunting season. Frank D. Haller was appointed study leader in March 1952 when the writer was transferred to the central office.

Deer counts made on Harrison State Forest indicated that the Blue River herd was reduced to one-fifth of its pre-season size. This amply demonstrated that we never need fear over-browsing and crop damage in Indiana, for the three-day "any-deer" season decimated this over¬crowded herd. Similar counts made on the Brown County State Park showed that this herd was half again as big as it had been the previous year. This increase resulted from movement of deer into the Park which served as a refuge during the hunting season. Thus the value of large refuges, where necessary, was demonstrated.

The study leader and conservation officers interviewed nearly 1,100 farmers and public employees in 23 counties comprising the principal deer range. Over half the interviews were obtained outside the 1949 herd range in order to find out whether the open season had scattered deer.

In the 17 counties in which the 1951 hunt was held, more deer were reported in, 1952 than in 1949. This was to be expected as 3 years of reproduction had ensued since the 1949 inventory. In these counties, four-fifths of the animals were recorded within the 1949 herd ranges, therefore, little range extension was evident. The computed fall popula¬tion in the 17 counties, based on the 1952 survey, was 3,307 deer. It was assumed that hunters had removed about a third of the animals in these counties during the 1951 hunt.

Crop damage complaints were considerably lower than in 1949 and more farmers said they would permit hunting in 1952 than previously. Approximately three-fourths of the farmers were in favor of a 1952 open season, but few independently suggested a buck season.

To sum things up, counts made after the hunting season showed that in 1952 there would be 28 per cent less deer available for hunters in 1952 in the 17 counties open in 1951.

Just as one swallow does not make a summer, one deer hunting season does not supply all the answers for herd management. Addi¬tional information has borne out the fact that small herds in terrain as that of Indiana cannot withstand consecutive "any-deer" seasons. It was found that herd centers were so saturated with hunters that nearly every deer Hushed was bagged before it ran the gauntlet. They are hunted rabbit-style and effectively so. Since there are no natural refuges comparable to swamps and pine thickets of the Lake states, a high percentage of those present may be taken in a short period. Per¬haps this would not be true if a large number of counties could be opened to disperse hunting pressure, or if a higher population was present. Since the Blue River herd was decimated and others had been reduced to the point where damage was infrequent, it was recommended that the season not be opened until herd recovery warranted it.

THE 1952 HUNT

An "any deer" hunt was held November 6 ,7, and 8 inclusive. In total, 18 counties were opened but Harrison and part of Crawford County which had been over-shot in 1951 were closed. In an effort to reduce the kill and as a safety factor, hunting hours were limited to 8 A.M. to 4 P.M. Otherwise, regulations remained the same as those of 1951.

A severe drought, hazardous forest fire conditions, and heavy hunt¬ing pressure detracted from the success enjoyed the previous year. In total 19,835 participating gun hunters bagged 1,112 deer, or put another way, about 6 per cent of the nimrods brought home meat. Archers, 117 of them, brought down 2 deer for a 2 per cent success.

The Strip Mine herd was severely depleted and the 8 A.M. to 4 P.M. hunting hours could not be enforced and met with considerable hunter opposition.

Resignation of Study Leader F. D. Haller and a shortage of con¬servation officers made it impossible to conduct counts to determine the full effect of the 1952 hunting season. On the basis of previous estimates, less the 1952 kill, plus 1953 reproduction, the 1953 fall population was estimated to 3,700 animals in comparison to 4,900 in 1951. Field obser¬vations, however, confirmed the belief that further herd reduction was inadvisable.

THE 1953 BUCK HUNT

The proper way to reduce herds where they have outgrown their range is to declare a dividend and permit hunters to kill "any deer," bucks, does, and fawns. The Department of Conservation realized that this is a management tool for herd reduction and could not be used unless a surplus existed and a reduction was warranted. Obviously, further reduction was not desirable in 1953. The Department had the choice of either closing the season as the investigation suggested or turning to a buck season. Since many does are bred by one buck, a hunt for antlered deer reduces the herd only by the actual number of bucks taken. Breeding takes place unaffected by the hunt and the fawn crop more than replaces antlered deer taken. One of the flaws in this kind of hunt is that antlerless deer are sometimes killed in error or viola¬tion and left to rot where they fall. Perhaps the greatest objection is the peril of public accustomed to the easy kills associated with "any deer" hunts, but not acquainted with the low hunting success characteristic of buck hunts. Few hunters realized that two-thirds of the herd consists of does and fawns even when there is a 50/50 ratio of bucks and does. Few take into consideration that the legal third of the herd, antlered bucks, are far more difficult to bag than does and fawns. A public un¬accustomed to relatively low kills of buck hunts in comparison to "any deer" hunts is usually quite disappointed and disgruntled after exper¬iencing its first buck hunt.

The Department of Conservation, believing that hunters would prefer a buck hunt to a closed season, decided to declare an antlered deer hunting season of short duration in December, 1953. Previous studies of reproductive organs obtained during the first two hunts showed that the breeding period occurred the same time as the hunt¬ing season and that because of this disturbance a number of does were not bred. Forest fire hazards, meat spoilage, and poor stalking condi¬tions combine to make November an undesirable time to hunt deer in this state. On December 4 and 5, male deer with at least one forked antler could be hunted in 12 counties from sunrise to sunset. Licenses were re¬stricted to residents of the state and only shotgun slugs could be used.

In total, 6,029 licenses were sold and 81 bucks bagged, yielding 1.3 per cent hunter success. Four checking stations examined only 13 ani¬mals in contrast with 631 in 1951 and 340 in 1952. Although hunters had been informed to expect low hunting success due to the nature of the season and scattered herds, a majority of them were greatly sur¬prised and disappointed at the low hunting success.

The bow and arrow season was liberalized to permit archers to hunt from November 23 to December 3 inclusive on 8,500 acres of Brown County State Park which is closed to gun hunting. This property has the greatest concentration of deer in the state and bucks with at least one forked antler could be taken. No deer were killed and archers be¬lieved that they were too crowded although there were 40 acres per hun¬ter if all of the 210 licensees were in the woods at the same time. In adjacent states an average of 5 acres per hunter is frequently found.

THE 1954 BUCK HUNT

The 2-day buck hunt initiated in 1953 was repeated in 12 counties in 1954 in lieu of a closed season. Bucks with at least one forked antler could be taken by shotgun slugs only between the hours of sunrise and sunset, December 3 and December 4. Of the 3,306 licensees, 68 reported bagging a buck, a success of 2.1 per cent compared with 1.3 per cent in a similar season in 1953. Buck hunts characterized by low hunting pressure and lower hunting success will be continued until widespread population expansion again warrants "any deer" seasons.

The archery season was opened on Brown County State Park from November 22 to December 2, inclusive, and bucks with at least one forked antler could be taken. The 186 participating bow and arrow hunters bagged one buck.

INDIANA'S WHITE-TAIL FUTURE

Many states have more deer in one county than we have in all 92. We will' never be able to produce and harvest them in numbers comparable to the Lake States. Deer like any other wildlife resource are a product of the land and in most of our range a by-product. Their numbers must be compatible with our way of life including farming, and forestry (Figure 11).

Sometimes the income derived from agricultural and forest prod¬ucts may be supplemented by that of wildlife resources. In resort areas, wildlife values often exceed those of forestry and agriculture. Deer have already made a contribution to farmers and business men in southern Indiana, and if the herds were permitted to increase they would be of far greater economic importance. Thus far, 41,000 hunt¬ers have participated in 4 short hunts totaling 10 days of hunting. In these 10 days, a total of 310,000 hunter man-days was spent afield. If each hunter spent only five dollars per day for food, lodging, gaso¬line, and amusement, a total of $1,550,000 was put into circulation.

If our deer had not been wantonly killed throughout the past 20 years, we could expect a herd exceeding 20,000 animals to be present today and recreational and economic values correspondingly greater than those derived from a herd of 4 or 5 thousand.

As has been pointed out, the reproductive power of whitetails is so great that with reasonable husbandry, our herd can expand to take its place as an important recreational and economic by-product. This expansion should be accomplished by spreading the herd over many counties suitable for deer in which few or none are present rather than permitting large herds to develop in a few relatively small areas (Figure 12).

When the time comes that a third or more of the counties can be opened to hunting, the pressure on landowners and herds alike will be diminished, thus relieving many of the conflicts stemming from crowded hunters.

Figure 12-Principal Deer Range 1955.

Under our present conditions "any deer" hunts are justified only in times and places where herd reduction is warranted. Buck hunts put less meat in the locker but are necessary if a hunt is to be held each year and the herd permitted. to increase to desirable proportions. When herds approach the point when severe damage is sustained to crops and woodlands, does and fawns, as well as bucks, should and will be again made legal game.

LITERATURE CITED

Allen, J. M. 1946-1955. Indiana Pittman-Robertson Quarterly Reports. Barnes, W. B. 1943. Indiana Pittman-Robertson Quarterly Reports. Haller, F. D. 1952-1953. Indiana Pittman-Robertson Quarterly Reports. Lyon, M. W., Jr. 1936. Mammals of Indiana. Univ. Press, pp. 1-384. Sandburg, Carl. 1939. Abraham Lincoln; the war years. Vol. I, p. 81. Brace & Co. Harcourt,

John M. Allen, Project Leader Project W-2-R

Most wildlife species present today have persisted because of, or In spite of numerous influences operating long before biolo¬gists were able to record them. We can only surmise how the passenger pigeon, bison, and otter reacted to the environment of Indi¬ana. Not so the white-tailed deer, for after being totally "wiped out" they were given a fresh start in 1934. This provided the rare opportunity of following the fortunes and misfortunes of this restored native. Ex¬periences of other states and information collected at home on our growing herd were pooled to prescribe management practices assisting the adjustments necessary before they could take their place as Indi¬ana's only big game animal.

Some progress has been attained in whitetail management, but it is doubtful if a permanent and unyielding solution for all ills will ever be formulated. It is hoped that we can anticipate problems associated with deer management and provide answers before difficulties arise.

As is the case with many wildlife species, management of the ani¬mal is far less difficult than associated problems of man-management. Until administrators, hunters, and landowners are aware of the poten¬tialities and reactions of growing deer herds, management recommen¬dations will be of limited value.

CHARACTERISTICS

Our white-tailed deer are members of a distinguished family in¬cluding elk, caribou, moose, mule deer, and black-tail deer. While there have been rumors of mule deer moving into our southern counties from releases in Kentucky, none have been found, and we can assume that our only deer is the whitetail. .

As to dimensions, ours are large in comparison to those of many other regions due to better food conditions; however, deer sizes are nearly always overestimated. Weights vary with sex and age of the animal, but average weights of approximately 1,000 adults and fawns, bucks, and does, examined at checking stations indicate that the "aver¬age" male weighed 157 pounds live weight and his female counterpart but no pounds. Three splendid bucks were taken during the 1951hunting season. One weighed 329 pounds before dressing; the other two were cleaned before weighing, but would have exceeded 300 pounds live weight.

One of the most interesting features of the male is his rack of antlers. Contrary to popular belief, they are not indicators of age, but rather they reflect the animal's physical condition. In general the diameter of antlers increases with age, but a well-fed 4 year old may have a much larger rack with more points than an 8 year buck in poor physi¬cal condition. Antlers fall off each year between January and March much in the same manner as do leaves. New ones start to emerge at once and quickly replace those lost but they remain soft until late sum-mer when they harden and are polished on small trees and bushes.

Deer, like cattle, have no front teeth on their upper jaw and break their food off rather than bite it. Similarly, they are ruminants and have 4 stomachs, but unlike most others they have no gall bladder. They frequently swallow acorns and grain whole, then regurgitate, chew, and swallow at their leisure.

Does are bred in October and November and after 205-212 days gestation, drop fawns. Their reproductive powers are usually under¬estimated as 25 does would have 3,000 descendants in 10 years if all survived. They add 25 to 35 per cent to their numbers each year thereby compensating for an annual loss by legal and illegal kills, dogs, and automobiles. In fact, when a herd is not increasing each year it indi¬cates a mortality factor worthy of investigation. It has been estimated that the 1955 Indiana herd should number 20,000 animals instead of 5,000. Illegal kills of both sexes were a serious limiting factor when the herd was first, becoming established a few years ago.

Their color changes with the seasons as their reddish summer coat is replaced by a gray one in autumn. Fawns are born with light colored spots on a brown background serving to camouflage them, but this coloration fades to match the gray of their parents in early fall . Deer were formerly regarded as an animal of the deep forests but their rapid increase throughout the Midwest in the past two decades has revised our ideas of what constitutes deer range. This is but another example of how some animals have adapted themselves to changing con¬ditions. They now thrive at the very edges of large metropolitan areas and inhabit farmlands boasting of little cover other than inconspicuous woodlots. When whitetails first began their population climb in Missouri, Ohio, Iowa, and other Midwestern states, game managers believed only hilly country could be occupied. Each year their range has been ex¬tended until now it is more difficult to predict where they will not thrive than where they will.

A deer's life can be a hazardous one for ancient predators such as wolves and mountain lions have been replaced by modem ones. Illegal killing of young and old throughout the year has, in some counties, prevented their increase and in a few has nearly destroyed the devel¬oping herds. Loose running dogs take their toll, particularly in the spring when does are heavy with fawns. It has been demonstrated many

times that hunting dogs of various breeds and curs can and do run down and kill even adult bucks. Many miscellaneous accidents such as drowning, collisions with fences and autos, and falls over cliffs are the result of dog chasing. These mortality factors are probably not too important to a large herd but seriously limit the successful establishment of small herds such as ours.

Open deer hunting seasons have probably helped deter illegal kills more than is commonly recognized. Merchants and farmers alike dis¬covered that a deer in the field is worth many in the meat house, as deer bring hunters, and hunters spend money. Increased efficiency of the enforcement section has paid off in a marked decrease in deer law violation. Considerable credit is due the group of conservation officers and forestry personnel who have contributed much to protect our herds.

Whitetails are primarily browsers although they graze winter wheat, rye and spring grasses. Their diet leans heavily towards leaves, fruits, and tender twigs of most common weeds, shrubs, and tree seedlings. Acorns are the backbone of their winter diet, but no one can deny that they turn readily to grain and hay and when the mast crop fails. Some damage to green corn and soybeans has been experienced in mid-summer in localized areas. Damage is most severe in small fields bordering wood¬lands and occurs most frequently during winter months so losses can be curtailed by harvesting crops as soon as possible after they ripen. Bucks like to polish their antlers on small trees and during the breeding sea¬son stage fights with imaginary opponents, usually small trees. Some damage to fruit trees has been caused in this manner and has been successfully prevented by spraying with commercial deer repellents and scaring devices such as foil streamers. Consumption of their pre¬ferred foods such as poison ivy, sassafras, mints, plantain, honeysuckle, greenbriar, sumac, and wild grape can scarcely be cause for complaint.

Disease and parasites have not been prevalent here nor responsible for deer loss. Lung worms, sometimes common in deer farther north have not been found here, and "hemorrhagic septicemia," the deer disease of the South, has occurred only on a small scale. They live to a ripe old age as shown by ear tagging those released. Two ear tags were returned by hunters in 1951 and one in 1952. These animals had been released in 1941 and were a year old at that time. Tame deer may live 15 years, but wild ones seldom escape the "grim reaper" that long. In the snow belt of states and provinces of the north, food supplies and snow drifts frequently determine how many deer can be carried through the winter. Deer congregate in "yards" and consume all avail¬able food in this limited area, causing the weaker ones to starve. Rela¬tively mild winters here permit deer to utilize the same range both winter and summer, and starvation is unknown.

EARLY HISTORY

At the time Indiana was settled, the northern whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus) was widely distributed over the state. This territory was covered with hardwood forest with the exception of the larger prairies, swamps, and lakes extending across the northern portion of the state. As many as 1,130 hides were purchased by a fur dealer in Hamilton County in 1859. Carl Sandburg's biography of Abraham Lincoln quotes as follows: "In 1820 Noah Major, one of the first settlers in Morgan County, Indiana, estimated there were 20,000 deer in the county." They were plentiful in the Kankakee region and there are reports of 65 being killed in a single day in 1878. The last stand of deer in the state was in the Kankakee region and in Knox County where the last known wild deer was killed near Red Cloud in 1893.

RESTOCKING

Removal of timber from steep hillsides produced violent results in the south central hill country. Farmland was soon abandoned as top soil washed away. Much remains in private ownership, but state and federal governments now own approximately 235,000 acres in this section.

In the early 1930's the Indiana Division of Fish and Game became interested in the possibilities of this territory for forest game. In total, 296 whitetails were released during the period 1934 to 1942 (Table 5). Of this number, 91 were released between 1934 and 1940 and 205 in 1941 and 1942. Many of the earlier releases were made on both state and privately owned land. Liberations were principally confined to the unglaciated hill country of the south central section, with minor releases to the east and west. Deer used for restocking were obtained primarily from Wisconsin but some were purchased from Michigan, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina. This stock was comprised of some southern whitetails, northern whitetails (Odocoilius virginianus borealis), and mixtures of these two sub-species.

Original liberations in the south central section were successful enough to initiate deer hunting there in 1951, where an open season has been held every year since that date. It soon became apparent that the limited occupied range could not accommodate all the hunters without greatly reducing the herd unless the season was limited in duration and sex to be hunted. The answer was to extend the occupied range so that hunting pressure could be dispersed over a much larger area. Surplus deer were removed from state owned exhibits in 1953 and 11 were released.

The Woodland Game Development Project purchased 100 white¬tails from the Schowalter Deer Farm in Wisconsin. These animals, half of which were does, were released on the east and west flanks of the occupied deer range in order to eventually provide more deer hunting territory.

Figure 7-0ne of the first deer releases. Harrison County State Forest 1934. (Photo by Dewey Hickman)

A release of 35 of these deer was made in Sullivan County on Greene-Sullivan State Forest where there is an abundance of suitable range in and surrounding this forest. In January 1955, a total of 26 was liberated on Shakamak State Forest in Sullivan County to further ex¬tend the herd in the southwestern portion.

In order to establish a herd in the southeastern section, 39 deer were released on Versailles State Park in Ripley County in February 1955 (Table 5). The counties in which these animals were released will be closed to deer hunting for a period of at least five years to per¬mit herds to develop. At the end of that period they and adjacent coun¬ties will be open to hunting if warranted by herd increases.

TABLE 5

WHITE-TAILED DEER LIBERATIONS IN INDIANA, 1934-1955

THE BEGINNING

Following the releases of 1941 and 1942, WID. B. Barnes started gathering information on the growth of our new herd. By interviews with local residents and state personnel, the 1944 population was found to be 1,200 animals as com-pared with 900 in 1943 (Figure 8). They had extended their range into 35 counties, three of which had herds of 60 to 100 deer. The headquarters for larger herds re¬mained on state forests or parks with the exception of small but growing herds in the strip mines of Pike and Warrick Counties and on private land in Orange County.

Few people, not intimately as¬sociated with deer, realize their reproductive powers. More than one-third of our female fawns are bred at the age of 6 months and have produced another fawn by the time they are a year old. Ma¬ture does nearly always produce twins each spring and triplets oc¬cur frequently. Barring excessive illegal kills, herds were destined to extend their range and numbers by leaps and bounds. By 1946 there were approximately 245 deer in counties outside principal deer range, while 18 counties within principal deer range, supported herds totaling 2,700 animals. This figure was conservative as some local residents and state employees believed that 500 to 1,000 animals were present on Brown County Park, with equal numbers on state forests, U. S. Forests, and U. S. Military Reservations.

A deer drive was conducted in November 1946 on Harrison State Forest with the aid of interested landowners and sportsmen. Seven bucks and 19 antlerless deer were Hushed from a 700 acre tract, con¬sidered to have been one of the most heavily populated ranges in the state. This would indicate 1 deer per 27 acres in part of the forest. If the entire forest was as heavily populated as the area driven, the forest population would have been 630 animals. Since a major portion of it supported a much lower population than the area driven, it is doubt¬ful if more than 350 animals were present in the entire county at that time.

Aerial deer counts have been utilized with varying degrees of suc¬cess throughout the nation, so in February and March 1947, this method of counting deer was tested on an experimental basis. Flights totaling 20 hours were made over Harrison State Forest, Brown County Park, and in Orange County. That observation prior to February was impaired by leaves remaining on trees of the white oak group. Cedar trees and pine plantations greatly limited observation where present. Under Indiana conditions, an aerial survey can be utilized only, if at least two inches of snow covers the ground, and if the wind velocity does not exceed 10 miles per hour. The experiment showed that the aerial census with conventional aircraft has very limited use over the major portion of our principal deer range.

By 1946 the novelty of seeing deer had passed. Damage to small grain, corn, hay, truck crops, and orchards was reported with increas¬ing frequency. A shootable population had developed in small seg¬ments of the range, but insufficient areas had reached this stage to justify the open hunting season. Illegal hunting became a problem of major importance.

COMPLICATIONS

The manner in which all animals, large or small, mesh into their environment is indeed complicated. In fact, many of the relationships between any game animal, and other plants and animals, including man, are unknown. It is understandable that re-introduction of even a native game animal is seldom accomplished without some conflict of interests.

In order to assist this adjustment it became apparent that the Con¬servation Department must collect as much information as possible on the growing herd. The White-tailed Deer Investigation was initiated in December 1949. This study was designed to map occupied deer range, to estimate herd size, and to devise methods of censuring deer on uninhabited forest tracts where farmer-interview census methods were not effective. Deer losses through illegal kills, dogs, and highway accidents were occurring at an unknown but increasing rate. Crop damage was severe in some localities but was greatly exaggerated and used as an excuse for illegal killing in widespread areas. We were now in the awkward position of having many deer in rather localized areas capable of sustaining crop damage, but not enough deer range to open a season so that legal hunters could scatter herds and reduce crop damage. It was necessary that hunt plans be formulated for the time that a hunting season could be held.

Eleven major herds were mapped in 1949 within principal deer range. Herd sites varied considerably in character, but they possessed one common feature-a refuge from men and dogs. None were formal inviolate tracts, but had been established for timber production, recrea¬tion, military use, private estates, or coal mining. Minor exceptions were portions of the Orange County and Muscatatuck herds.

The Morgan-Monroe herd became established on Morgan-Monroe State Forest, and occupied parts of Morgan, Monroe and Brown Coun¬ties. The Brown County herd developed in Brown County State Park and extended into Lawrence, Jackson, and Brown Counties. The Mus¬catatuck-Knobs herd started from deer released on Jackson and Clark State Forests, and by 1949 projected into 6 counties. The Orange ¬Martin herd extended into Lawrence, Greene, Martin, and Orange Counties. The Blue River Herd was located in both Harrison and Craw¬ford Counties, but was restricted largely to Harrison State Forest. The Lafayette Herd was limited to Perry County and originated from re¬leases made on U. S. Forest Service land . The Ferdinand herd was developed on Ferdinand State Forest in Dubois County, but extended into Perry County. The Strip Mine herd centered on coal company land in Pike, Warrick, Dubois, and Gibson Counties.

Farmers were interviewed throughout the deer range in 1950 to determine the extent of deer damage to crops, to obtain their opinions on an open season, and to estimate deer numbers. About two-thirds of them had never sustained damage, three-fourths favored an open season, and nine-tenths of them were in favor of having deer in their area.

The 1949 population census showed 2,540 animals, of which 300 were in counties scattered over the state and outside the principal range in the south-central hill section. Due to illegal killing of bucks and does, young and old, there were fewer deer in 6 counties than in 1946, but most of the herds showed a gain.

FIRST OPEN SEASON

The White-tailed Deer Investigation had progressed to the point in 1951 that we knew where the deer were, approximately how many, something of their rate of increase, and limiting factors. Many of the basic facts necessary for proper management were still unknown but it became increasingly apparent that an open hunting season was needed to scatter herds, relieve crop damage, and curb illegal kills. The 1951 population estimate was 4,943 animals, quite an increase from 1944. About 4,500 of these were in 17 counties which were believed to be ready for an open season.

The 1951 General Assembly gave the Director of the Division of Fish and Game discretionary powers to issue orders regulating the hunting and killing of deer. A hunt plan including regulations was form¬ulated and submitted to the Director of Fish and Game.

The first open deer hunting season in 58 years was held November 1, 2, and 3, 1951. In brief, it was an "any deer" season in 17 counties, with shotgun slugs and bow and arrows only. The number of licenses sold was not limited. They were issued at a cost of five dollars to resi¬dents only. Information on the hunt was collected by compulsory re¬turn of postal card reports issued with licenses, while Pittman-Robertson personnel and conservation officers manned 6 checking stations in 5 herd areas where successful hunters were interviewed and deer examined.

Nearly everyone agreed that the open season was an unqualified suc¬cess. Consideration and cooperation of hunters and landowners was above reproach. It was characterized by splendid landowner-hunter relations, a high degree of gun safety was maintained, and hunters were well pleased. In total 633 deer were brought to checking stations where they were hog-dressed, weighed, and age determined by tooth-wear charts. In total. 12,182 licenses were sold; 10,002 licensees returned hunt reports.

Farmers hunting on their own land without licenses were reported by conservation officers to have killed 32 animals. Licensees reported bagging 1,558, thus the total known kill was 1,590 bucks, does, and fawns. This indicates that 13 per cent of the licensees were successful. Bows and arrows could be used in any of 17 open counties and approxi¬mately 8,600 acres of Brown County State Park were open to archery hunters only. Three deer were taken by archers, one by a 14 year old lad. About half the deer taken were bagged on the first day of the hunt, while on the second and third days, 24 per cent and 25 per cent were recorded. Greatest success was attained between 7 A.M. and 11 A.M., as more than half of the kills were made during these hours.

Based on interviews of 633 successful hunters, each man hunted about a day and a half, saw 3 1/2 deer, shot at I 1/2, and hit one. The average range on the first shot was 48 yards. Evidently the shotgun slug was effective, for 47 per cent of the animals dropped in their tracks, 36 per cent ran 1 to 50 yards, 15 per cent ran from 51 yards to a half mile, and 2 per cent ran farther than a half mile before dropping.

Adult bucks comprised 39 per cent of the kill; adult does, 30 per cent; and fawns, 31 per cent. Considering both adult and fawns, bucks constituted 55 per cent of the kill.

Both entire and hog-dressed animals were brought to checking stations for examination. Weights before and after hog-dressing, in¬cluding removal of heart, liver, and lungs, indicated that adults lost approximately 18 per cent, and fawns 20 per cent in gutting. Total length from tip of nose to tip of tail bone and hind foot measurements were taken to compare skeletal development of deer in different herds. Antler development was similarly utilized to compare condition of the animals and indirectly indicated the quality of range used by different herds. A number of bucks with 16-20 antler tines was recorded. Spurs on freak sets were not counted as points.

The most outstanding fact revealed by this intonation was that deer from the Blue River herd were smaller boned and weighed less than those of the other 4 herds sampled. It had been suspected that this area was overpopulated and that over-browsing was becoming an immediate problem. The superiority of the mixed range of the Strip Mine herd was reflected in above average weights and measurements in most age classes. Bucks continued to gain weight until about 7 ½ years old, but does weighed nearly as much when 2% years old as did older specimens.

A number of large animals was taken from all herds. Bucks in the 5 ½ year age class from all areas averaged 191 pounds dressed and had 10 antler points, while those in that class from the Strip Mine herd averaged 243 pounds. One buck examined at Morgan-Monroe State Forest weighed 270 pounds and another 269 pounds dressed. The largest doe examined was taken from the Strip Mine herd; was 2 ½ years old; and weighed 156 pounds dressed, or 190 pounds live weight. The weight of deer is usually overestimated as four and five hundred pound bucks reported by local residents did not materialize at the scales.

The immediate task of the deer investigation was to evaluate the effects of the first hunting season. Frank D. Haller was appointed study leader in March 1952 when the writer was transferred to the central office.

Deer counts made on Harrison State Forest indicated that the Blue River herd was reduced to one-fifth of its pre-season size. This amply demonstrated that we never need fear over-browsing and crop damage in Indiana, for the three-day "any-deer" season decimated this over¬crowded herd. Similar counts made on the Brown County State Park showed that this herd was half again as big as it had been the previous year. This increase resulted from movement of deer into the Park which served as a refuge during the hunting season. Thus the value of large refuges, where necessary, was demonstrated.

The study leader and conservation officers interviewed nearly 1,100 farmers and public employees in 23 counties comprising the principal deer range. Over half the interviews were obtained outside the 1949 herd range in order to find out whether the open season had scattered deer.

In the 17 counties in which the 1951 hunt was held, more deer were reported in, 1952 than in 1949. This was to be expected as 3 years of reproduction had ensued since the 1949 inventory. In these counties, four-fifths of the animals were recorded within the 1949 herd ranges, therefore, little range extension was evident. The computed fall popula¬tion in the 17 counties, based on the 1952 survey, was 3,307 deer. It was assumed that hunters had removed about a third of the animals in these counties during the 1951 hunt.

Crop damage complaints were considerably lower than in 1949 and more farmers said they would permit hunting in 1952 than previously. Approximately three-fourths of the farmers were in favor of a 1952 open season, but few independently suggested a buck season.

To sum things up, counts made after the hunting season showed that in 1952 there would be 28 per cent less deer available for hunters in 1952 in the 17 counties open in 1951.

Just as one swallow does not make a summer, one deer hunting season does not supply all the answers for herd management. Addi¬tional information has borne out the fact that small herds in terrain as that of Indiana cannot withstand consecutive "any-deer" seasons. It was found that herd centers were so saturated with hunters that nearly every deer Hushed was bagged before it ran the gauntlet. They are hunted rabbit-style and effectively so. Since there are no natural refuges comparable to swamps and pine thickets of the Lake states, a high percentage of those present may be taken in a short period. Per¬haps this would not be true if a large number of counties could be opened to disperse hunting pressure, or if a higher population was present. Since the Blue River herd was decimated and others had been reduced to the point where damage was infrequent, it was recommended that the season not be opened until herd recovery warranted it.

THE 1952 HUNT

An "any deer" hunt was held November 6 ,7, and 8 inclusive. In total, 18 counties were opened but Harrison and part of Crawford County which had been over-shot in 1951 were closed. In an effort to reduce the kill and as a safety factor, hunting hours were limited to 8 A.M. to 4 P.M. Otherwise, regulations remained the same as those of 1951.

A severe drought, hazardous forest fire conditions, and heavy hunt¬ing pressure detracted from the success enjoyed the previous year. In total 19,835 participating gun hunters bagged 1,112 deer, or put another way, about 6 per cent of the nimrods brought home meat. Archers, 117 of them, brought down 2 deer for a 2 per cent success.

The Strip Mine herd was severely depleted and the 8 A.M. to 4 P.M. hunting hours could not be enforced and met with considerable hunter opposition.

Resignation of Study Leader F. D. Haller and a shortage of con¬servation officers made it impossible to conduct counts to determine the full effect of the 1952 hunting season. On the basis of previous estimates, less the 1952 kill, plus 1953 reproduction, the 1953 fall population was estimated to 3,700 animals in comparison to 4,900 in 1951. Field obser¬vations, however, confirmed the belief that further herd reduction was inadvisable.

THE 1953 BUCK HUNT

The proper way to reduce herds where they have outgrown their range is to declare a dividend and permit hunters to kill "any deer," bucks, does, and fawns. The Department of Conservation realized that this is a management tool for herd reduction and could not be used unless a surplus existed and a reduction was warranted. Obviously, further reduction was not desirable in 1953. The Department had the choice of either closing the season as the investigation suggested or turning to a buck season. Since many does are bred by one buck, a hunt for antlered deer reduces the herd only by the actual number of bucks taken. Breeding takes place unaffected by the hunt and the fawn crop more than replaces antlered deer taken. One of the flaws in this kind of hunt is that antlerless deer are sometimes killed in error or viola¬tion and left to rot where they fall. Perhaps the greatest objection is the peril of public accustomed to the easy kills associated with "any deer" hunts, but not acquainted with the low hunting success characteristic of buck hunts. Few hunters realized that two-thirds of the herd consists of does and fawns even when there is a 50/50 ratio of bucks and does. Few take into consideration that the legal third of the herd, antlered bucks, are far more difficult to bag than does and fawns. A public un¬accustomed to relatively low kills of buck hunts in comparison to "any deer" hunts is usually quite disappointed and disgruntled after exper¬iencing its first buck hunt.

The Department of Conservation, believing that hunters would prefer a buck hunt to a closed season, decided to declare an antlered deer hunting season of short duration in December, 1953. Previous studies of reproductive organs obtained during the first two hunts showed that the breeding period occurred the same time as the hunt¬ing season and that because of this disturbance a number of does were not bred. Forest fire hazards, meat spoilage, and poor stalking condi¬tions combine to make November an undesirable time to hunt deer in this state. On December 4 and 5, male deer with at least one forked antler could be hunted in 12 counties from sunrise to sunset. Licenses were re¬stricted to residents of the state and only shotgun slugs could be used.

In total, 6,029 licenses were sold and 81 bucks bagged, yielding 1.3 per cent hunter success. Four checking stations examined only 13 ani¬mals in contrast with 631 in 1951 and 340 in 1952. Although hunters had been informed to expect low hunting success due to the nature of the season and scattered herds, a majority of them were greatly sur¬prised and disappointed at the low hunting success.

The bow and arrow season was liberalized to permit archers to hunt from November 23 to December 3 inclusive on 8,500 acres of Brown County State Park which is closed to gun hunting. This property has the greatest concentration of deer in the state and bucks with at least one forked antler could be taken. No deer were killed and archers be¬lieved that they were too crowded although there were 40 acres per hun¬ter if all of the 210 licensees were in the woods at the same time. In adjacent states an average of 5 acres per hunter is frequently found.

THE 1954 BUCK HUNT

The 2-day buck hunt initiated in 1953 was repeated in 12 counties in 1954 in lieu of a closed season. Bucks with at least one forked antler could be taken by shotgun slugs only between the hours of sunrise and sunset, December 3 and December 4. Of the 3,306 licensees, 68 reported bagging a buck, a success of 2.1 per cent compared with 1.3 per cent in a similar season in 1953. Buck hunts characterized by low hunting pressure and lower hunting success will be continued until widespread population expansion again warrants "any deer" seasons.

The archery season was opened on Brown County State Park from November 22 to December 2, inclusive, and bucks with at least one forked antler could be taken. The 186 participating bow and arrow hunters bagged one buck.

INDIANA'S WHITE-TAIL FUTURE

Many states have more deer in one county than we have in all 92. We will' never be able to produce and harvest them in numbers comparable to the Lake States. Deer like any other wildlife resource are a product of the land and in most of our range a by-product. Their numbers must be compatible with our way of life including farming, and forestry (Figure 11).

Sometimes the income derived from agricultural and forest prod¬ucts may be supplemented by that of wildlife resources. In resort areas, wildlife values often exceed those of forestry and agriculture. Deer have already made a contribution to farmers and business men in southern Indiana, and if the herds were permitted to increase they would be of far greater economic importance. Thus far, 41,000 hunt¬ers have participated in 4 short hunts totaling 10 days of hunting. In these 10 days, a total of 310,000 hunter man-days was spent afield. If each hunter spent only five dollars per day for food, lodging, gaso¬line, and amusement, a total of $1,550,000 was put into circulation.

If our deer had not been wantonly killed throughout the past 20 years, we could expect a herd exceeding 20,000 animals to be present today and recreational and economic values correspondingly greater than those derived from a herd of 4 or 5 thousand.

As has been pointed out, the reproductive power of whitetails is so great that with reasonable husbandry, our herd can expand to take its place as an important recreational and economic by-product. This expansion should be accomplished by spreading the herd over many counties suitable for deer in which few or none are present rather than permitting large herds to develop in a few relatively small areas (Figure 12).

When the time comes that a third or more of the counties can be opened to hunting, the pressure on landowners and herds alike will be diminished, thus relieving many of the conflicts stemming from crowded hunters.

Figure 12-Principal Deer Range 1955.

Under our present conditions "any deer" hunts are justified only in times and places where herd reduction is warranted. Buck hunts put less meat in the locker but are necessary if a hunt is to be held each year and the herd permitted. to increase to desirable proportions. When herds approach the point when severe damage is sustained to crops and woodlands, does and fawns, as well as bucks, should and will be again made legal game.

LITERATURE CITED

Allen, J. M. 1946-1955. Indiana Pittman-Robertson Quarterly Reports. Barnes, W. B. 1943. Indiana Pittman-Robertson Quarterly Reports. Haller, F. D. 1952-1953. Indiana Pittman-Robertson Quarterly Reports. Lyon, M. W., Jr. 1936. Mammals of Indiana. Univ. Press, pp. 1-384. Sandburg, Carl. 1939. Abraham Lincoln; the war years. Vol. I, p. 81. Brace & Co. Harcourt,